This is the video and transcript of my recent conversation with Chris Nicholson on how the war in Ukraine will end. The video includes a map we review as we discuss the battlefield situation. See here for the audio of the conversation in podcast form. The transcript below is lightly edited for clarity and begins after the show notes and links.

Show notes:

Chris Nicholson is back on to talk about the war in Ukraine, this time with a specific focus on how the conflict might end. We start by discussing the Ukrainian capture of Kherson, and Chris puts forth the theory that Russia pulled back from the city in order to focus on the capture of the entirety of Donetsk province.

We go through different scenarios of how the war might move towards its end, whether through a Ukrainian victory or something of a stalemate, which is the best Chris believes the Russians can hope for in the short- to medium-term. Over the course of the conversation, we realize that Chris and I have very different intuitions about the likelihood of the West pulling its support for Ukraine. I think that if the war ends anytime soon, it’ll be because Ukraine wants to move towards peace, while Chris thinks that the US and Europe might nudge it in that direction. In my view, Ukraine has a blank check as long as it’s willing to fight and die. As I told Chris, I defer to him on battlefield questions, but I trust my own judgment on American politics.

We recorded this conversation on Monday, November 14, so before the deaths of two people in Poland yesterday from what was first thought to have been a Russian missile, but may have been fired by Ukraine in self-defense instead. The latest news is a reminder of the ever-present danger of escalation, and why it’s important to think carefully about how we can get to a settlement of the conflict.

Links and Previous Discussions on Ukraine:

“Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, November 13.”

“US privately asks Ukraine to show it’s open to negotiate with Russia.”

“The Impact of Winter, and Iranian Drones and Missiles” (Discussion with Chris, on October 24, 2022, audio and video)

HIMARS as Miracle Weapons (Discussion with Chris, October 3, 2022, audio)

Kherson and Other Developments

Richard: Hi, everyone. Welcome to the podcast. I'm here today with my friend Chris Nicholson. We’re recording this on...and this matters. This war sometimes has some very quick developments. We're recording this on November 14th, 2022 at around 6:30 Eastern Time. And today, we’re going to talk about just the recent developments. Recently we had the Russian withdrawal from Kherson. And then we’re going to spend, I think a lot of time talking about how this war is going to end and the potential outcomes, sort of a time scale that we’re looking at. So Chris, the Russians have retreated from Kherson. That’s the big news. Can you just tell us what happened here and what's going on elsewhere on the front?

Chris: Sure. So I’m still trying to figure out what exactly happened. The fog of war has been very heavy around the Kherson region for the last month or so, and it’s just beginning to lift now. What I can say is that things aren’t adding up. What has happened is not what Ukraine told us was going to happen. Basically, what’s going on? Rewind a few weeks. Rumors started to come out that Russia was beginning to withdraw. And then at every step of the way over the last couple weeks, Ukraine has responded saying, “No, that’s false. We don’t see any evidence of Russia withdrawing. In fact, we see evidence of them reinforcing, sending more mobilized men in. We think this is a trap. That’s why we’re not going to advance. We’re going to go very slow and it's going to be... There’s still 20 to 30,000, maybe even 40,000 Russians on the West Bank of the river. And it’s going to be a hard months long battle, maybe urban warfare for the city.”

And talking today, it seems clear that none of that ended up being true. That’s not how things in fact went down. In fact, it seems that within a matter of days after Russia made the official announcement that it was going to withdraw, Ukraine had all this territory and it didn’t actually seem like there was that much fighting. And it doesn’t seem like there’s that much mopping up action going on right now.

So I’m left with two main options to consider. Option number one is that Russia successfully fooled Ukraine, that Russia somehow deceived Ukraine into thinking that Russia was not withdrawing and was reinforcing, when in fact it was withdrawing. There are some stories starting to come out of stuff like Ukrainians discovering mannequins in the city of Kherson. Option number two…

Richard: Mannequins just standing around as troops?

Chris: Sorry?

Richard: Mannequins just like pretending to be soldiers?

Chris: Yeah.

Richard: They would need a lot of mannequins, right? There would have to be a satellite photo that can see the mannequins but not good enough to see that they’re not real.

Chris: It’s pretty hard for me to believe that Russia successfully deceived Ukraine and all of Western intelligence on such a large scale, which leads me to favor option number two, which is that Russia wasn’t deceiving Ukraine. Ukraine and Russia together were deceiving us, were deceiving the public, leading us to expect that there would these be this big long slog, this slugfest over Kherson when in fact maybe the two sides had negotiated and agreed on a withdrawal where Ukraine perhaps would allow Russia to withdraw in good order and in return it would preserve the city from devastation, and it would save it, the urban warfare, which would’ve potentially razed it, much of it to the ground. I think that’s looking more likely at this point.

Richard: What does each side get? Ukraine gets to take over the city without fighting and then Russia gets its...Both sides know what the outcome is going to be. Russia gets to preserve its troops and equipment. So it makes sense I guess for Russia, I mean for Ukraine, if they have a chance to destroy, to kill a lot of Russians and then also seize a lot of equipment. Wouldn’t they just want to do that instead of making a deal?

Chris: From a pure military perspective, I think yes, but it may be the interest of the civilians that made Ukraine potentially take some kind of deal like this where they didn’t want the civilians to suffer. They didn’t want the city to be burned to the ground basically. The main benefit to Ukraine would be sparing the civilians.

Richard: Okay. So I guess that makes sense. In your view, would this be a sign of a broader deal or do you think it’s just limited to Kherson?

Chris: I don’t think there’s any reason to suspect if there was a deal that it was broader. Another thing to add here, we had all those reports over the last couple weeks of Russia evacuating civilians from Kherson. I’ve seen the theory bandied about, and it sounds plausible that maybe some of those civilians were being used as shields for soldiers that were being evacuated.

I mean, honestly, that’s the way I would do it if I were Russia. That’s how you can be sure you can get your soldiers out without them being bombed the entire way. So we are getting some reports. We see some signs of Russian losses in this withdrawal, reports of a few dead Russians washing up on the riverbank, isolated captures here and there of an S-300 system, of some fancy artillery here and there. But I think so far we have reason to believe that the Russians did withdraw in pretty good order and they did not suffer massive losses in men or material, the same way they did in the Kharkiv counteroffensive.

So we’ll have to wait and see what information comes out. We may not know the full story for a long time, but what we can say with certainty is that this quick takeover of Kherson and this quick withdrawal, that is not at all consistent with what Ukraine had been telling us over the last several weeks.

Richard: Right. Okay. So that’s the Kherson region. What else? Is there anything else that’s worth noting about what’s going in the field...

Chris: Yeah. So sticking with this region for a bit. Couple things. So first, there are…

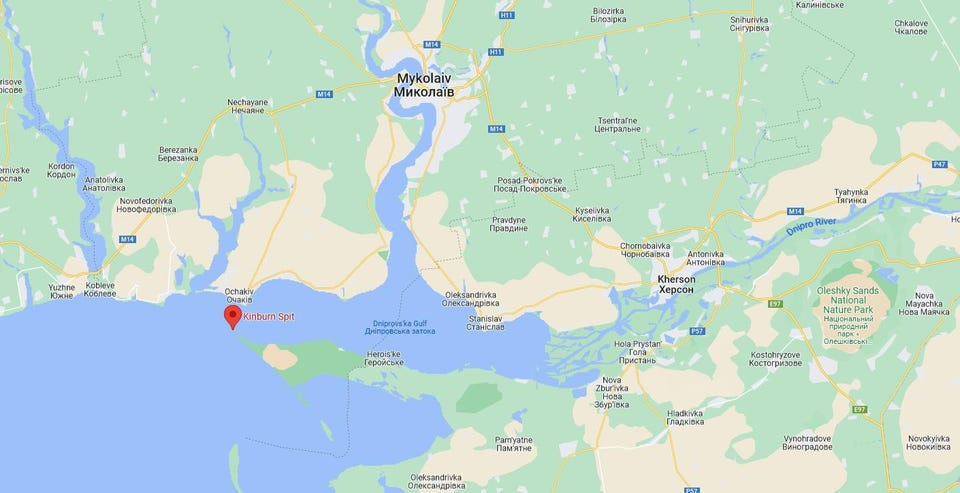

Richard: We have maps, by the way here, for people who are just listening on the podcast. So the video, if you want to watch the video, you could see all this. But go ahead Chris.

Chris: So first of all, there have been a lot of reports, rumors that are becoming steadily more real. I mean, Forbes just said it recently, reports of Ukrainian special operations forces being active right here on what’s called the Kinburn Spit to the south of Kherson across the river. And so that's interesting. I saw some videos that was reported to be Ukrainian special ops guys on inflatable boats crossing over to this region.

There are more rumors, these ones less substantiated, but there are rumors of Ukrainians taking a couple towns across the Dnieper River, which would be shocking to me. I think that probably in a day or two we’ll probably realize that Ukraine has not in fact been taking a town or two across the river. But that those kinds of rumors are caused oftentimes by special operations activity. A raid on a town can easily be transformed by rumor into taking over a town.

So I think that probably what’s happened is that the Ukrainians have taken a little bit of territory on the Kinburn Spit and that has some strategic value that we should talk about and they’re kind of creating a little beachhead here and using that to launch special operations raids into Russian territory.

Richard: Yeah. So talk about the strategic significance of... What is it called, the Krinberg? What did you say it was?

Chris: The Kinburn Spit.

Richard: Kinburn Spit. And for those who are not watching, it’s like a little thing that's jutting out into the Black Sea, south of Kherson.

Chris: A little peninsula. So the significance of it is that it’s going to be very hard for the Ukrainians to cross the Dnieper River to try and continue this advance. And it’s probably not going to happen. The Russians have been building up several defensive lines behind the East Bank of the river for quite a while now.

So for the most part, I think what we’re going to see is the Ukrainians are not really going to advance. The river will be a good barrier. I think that both the Russians and the Ukrainians are recognizing that fact and they're both rapidly diverting their forces away from this region to go fight on other fronts, which we’ll talk about. But I think what’s going on here, this activity on the Kinburn Spit, the Russians have been building all these defenses along the north of that, along the Dnieper River.

I think basically the Ukrainians are seizing this opportunity to establish a little beachhead here because Russia has not been constructing defenses from this region. So if Ukraine has a little beachhead here, it can launch raids. It can potentially land more guys. The Russians don’t have strong defenses here. So what this does is it gives the Ukrainians an opportunity to flank the Russians.

The Russians have to respect that threat. And so I think the main goal is for the Ukrainians to keep harassing the Russians, to force them to locate defenders here instead of moving them to where the new fighting is about to start.

Richard: And this spit down here, are there roads? I mean, are there roads that take you there from up to northeast where you'd want to go?

Chris: I think this region, I think there’s a lot of swamp here. You can see it’s called the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve. I think this region is very swampy, which means that it’s going to be hard for the Russians to dislodge the Ukrainians.

Richard: But it’s also hard for the Ukrainians to make an offensive, right?

Chris: Well, it’s going to be easy for them to get here. It may be hard for them to move a lot of equipment. I don’t think this is the kind of region where there are a lot of roads. So you probably can’t be taking a lot of armor through here. By the way, it’s been easy for Ukraine to grab this region because every bit of artillery Ukraine has is within range of it from the opposite shore.

So that’s basically why I’m confident that Ukraine, there really is fire to this smoke behind these rumors. Ukraine probably does have guys, special ops guys that have seized this land and are launching raids from it. And by the way, you can see all these explosions popping up here. You measure this distance from Ukrainian territory to where these explosions today are. This basically turns out to be HIMARS/GMLRS range.

So this is pretty much what we would expect to see. And this is a theme that we’ll kind of revisit throughout today’s podcast. What’s going to happen in the war? Who’s going to have to surrender what? Who’s going to be able to win what? Basically, a lot of it traces down to what is within HIMARS range. That’s the short of it. So since Ukraine has seized this territory, what we already begin to see happening is Russia is having to relocate all of its ammo depots and a lot of its command posts. It’s got to relocate all of that out of HIMARS range and that’s what these explosions are showing you.

Richard: The fortifications that Russia has on the east side of the river, what are they? I mean, do you know what they look like and could HIMARS blow them up? Is that possible?

Chris: Well, it’s just a series of trenches mostly.

Richard: And so there’s guys…

Chris: They’re not really a tempting target for HIMARS. I mean, yeah, you can use the M30A1 tungsten pellet ammo to get at some guys who are in those trenches.

Richard: So they’re in the trenches…

Chris: I don’t think that we’re going to see Ukraine crossing the river in any force. I think the frontline will be pretty much frozen here for the duration.

Richard: But coming up from that swamp for a large-scale sort of attack, that doesn’t sound very likely either. Sounds like…

Chris: It doesn’t. So I think that this is mainly going to be a location where Ukraine lands special ops forces to filter out on small teams and launch raids into this Russian territory.

Richard: But raids to what end? I mean if they’re…

Chris: To harass them and potentially what Russia has to be on the lookout for is the raids here could potentially weaken fortifications, weaken defenses along the Dnieper River. And if Russia isn’t careful, then the defenses could be weakened enough that Ukraine could launch a mass assault across the river. So this is something that I think Russia can defend against. I don’t think that the activity here will change the outcome of the war. I think ultimately the goal is for Ukraine to use a small amount of force here to force Russia to divert a relatively large amount of force to defend the region. I think that’s the game, basically.

Richard: Okay. Anything else on the Kherson front?

Chris: That’s everything I had to say about there. Now, as to the question of what’s going to happen next? Well, basically the front in this war, although still large, has shrunk significantly. We can rule out this entire region of the front now. We're not going to see that much more activity besides that harassment I talked about. And so now all the action is…

Richard: I’m sorry. One more thing. Ukraine is on the east side of the Dnieper. You can’t see my finger, but can’t they attack south from the east side of the river and then get to outflank them?

Chris: Attack south from where?

Richard: No. Zoom out a little bit. Zoom out to where we were. Okay, so you see the city Orikhiv. Do you see Orikhiv?

Chris: Yep.

Richard: Okay. Why can’t it go that way? There's already Ukraine on the east side of the Dnieper. All it has to do is go south and southeast. That could be another front, right? That’s just another front...

Chris: Sure. This is kind of the big question because there aren’t that many areas where the fighting can go next. I classify maybe three areas and two of the areas there’s already fighting. Area one, Ukraine is on the offensive up in Svatove and Kreminna in the Luhansk region. Area two, Russia continues to be attacking in the Donetsk region.

Now, the third region that’s relevant now is the Zaporizhzhia region in the south. And here Russia has been launching a few token attacks, some more intense than others, but this has been the least active region of the front. Ukraine has been hinting at a possible offensive in the Zaporizhzhia region to potentially go all the way to Mariupol. And the question is just, is that threat going to materialize? Are they going to go there next to, or are they going to send the extra reinforcements up to reinforce that counteroffensive in Luhansk? Are they going to send them to Donetsk? That is an open question.

But certainly there is a lot of strategic value to launching an offensive in Zaporizhzhia. I mean, look, if they managed to just cut down all the way to the sea in any of these regions that would be devastating for Russia because forget attacking this whole area. Forget attacking the remaining territory Russia controls in the south. If Ukraine just takes anything in here and holds it, then it can just choke all of this, completely starve it, and then Russia loses all of it. So that’s just the strategic value. Of course Russia knows that. And so its defenses are quite strong in this region.

Richard: Yeah. Has Russia in your mind given up any hope of taking new territory? Because it seems like there’s not much talk of that happening. Is that where we are?

Chris: That’s a good question. I think Russia has not at all given up hope. I was actually reading a good bit of analysis on this from the Institute for the Study of War in its update yesterday. And it reported this interesting theory. The new head Russian general. Do you know how you say his name? What is it? Surovikin?

Richard: No, I don’t know how to say it.

Chris: Okay. Well, I’ll say Surovikin. The head Russian general, new guy who was recently appointed. The theory they were saying was that he told Putin immediately that he wanted to withdraw from Kherson. And that Putin basically struck a deal with him saying, “I’ll let you withdraw only if you attack and succeed in taking all of Donetsk.” That theory explains why for the past few weeks, Russia has been furiously launching attacks in Donetsk to no real success and a lot of losses. The Institute for the Study of War was offering a theory that this is basically about politics, not about tactics.

Richard: And they’ve got a ways to go for Donetsk, don’t they? They have to get to, I think, Kramatorsk, which looks like, I don’t know how many miles that is, but it looks like a pretty... Are they making progress on the Donetsk front? Do you see them launching attacks?

Chris: They’re very halting. I mean, nothing really worth mentioning. I mean, if you were to look at this map, it’s basically the same as it looked several months ago.

Richard: So what’s the theory? Because the Ukrainians, they cut off the Russian supply lines. What’s the Russian theory for ... I mean, Ukraine has manpower and has weapons and has men. What’s the theory of how it could achieve a breakthrough here? Is it the mobilization? Is it just getting enough manpower?

Chris: The mobilization plus using the withdrawn troops from Kherson to reinforce it in this. And so the Institute for the Study of War was offering the theory that basically the new general, Surovikin, he was doing these premature attacks in Donetsk to assure Putin that he was serious in his promise that he was really going to go on the offensive in Donetsk. Like, “Hey look, we're doing it now. We’re already attacking. We’ll keep attacking.”

Richard: And this is important politically because Putin wants Donetsk and Luhansk at least. I mean, at least Donetsk and Luhansk probably to make this thing seem like it was worthwhile while Kherson is just... I mean it’s stupid because they annexed all of them. But Kherson seems like less of a natural goal than finishing the job in Donetsk, right?

Chris: Yeah. So I think Russia is just going to continue attacking here. It’s interesting every step of the way how much politics overrides tactics and strategy in this war. And I think that’s true for both sides. There are many political considerations. For Russia, it’s launching ineffective piecemeal attacks here, largely for political reasons. It’s kind of a military-political compromise. And because of that, it’s been piecemeal, Russian mobilized men in with little training, just throwing them into existing units and sending them into the woodchipper. I think it’s in Ukraine’s interest to basically let that continue. If Ukraine keeps the pressure up, that forces Russia to keep sending its mobilized guys in a trickle before they’re fully trained.

Richard: Yeah. That makes sense. Okay. You said Ukraine was making some progress on the northern front. How much have they made recently?

Chris: Not that much really. I mean look, I think it’s a kind of a similar situation to the Russian progress in Donetsk. I mean it’s pretty minimal. This line of control has not appreciably changed in the last couple of weeks.

Richard: So was Kherson maybe the last major... I mean, could it be just now that the lines are going to stabilize and Kherson was sort the last.. it was sticking out because they had the supply problems, but everything else is close to Russia. They have the manpower. They have a smaller space. They’re closer to Russia. Maybe there’s just no more advances?

Chris: That’s an important question and it’s up for debate. I think that there is one side that says, yeah, this is basically all the major progress we’re going to see for a while. And one strong voice, American voice on this side is I think General Milley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. I think he was in the news recently saying that he thinks that Ukraine has made all the big advances it’s going to make for a while. And so Milley is a strong voice starting to publicly pressure Ukraine to come to the negotiating table.

Richard: Do you take that at face value? I just see they’re playing good cop, bad cop. I don’t think Milley goes out and says things on his own, just his opinion. I think it’s part of an administration strategy.

Chris: It’s possible. It’s possible. Are you saying Biden has whispered to Milley, “Hey, you go out there saying that you think Ukraine could negotiate and then I’ll smack you down in the news. I’ll say no.”

Richard: Yeah, something like that. I don’t think…

Chris: Nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine.

Richard: Yeah. I don’t think the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff freewheels and goes on his own and just says whatever he thinks.

Chris: It is interesting that he seems at least publicly to be sticking out like a sore thumb. Maybe you’re right that maybe he’s under secret orders from Biden to play the bad cop here. That would still suggest that Biden himself on some level might think that Ukraine has made all the major gains it’s going to make.

Richard: Maybe. I mean, Washington Post, they were saying that the Biden administration was saying this because they were telling Ukraine to say this because they wanted Ukraine to maintain the idea that they had the moral high ground in international politics so they wouldn’t lose support. That's what The Washington Post is saying. But even that is probably... That’s something that I think the Biden administration would want to get into the The Washington Post. So it’s complicated. It’s like, do they really want negotiations or do they not? We don’t know what they think or it seems like... We know what they want us to think, but we can’t be sure what they really do think.

Chris: Well, Ukraine has been saying some pretty confident things. It’s been getting more and more hardline in its public positions as it’s gained more momentum on the battlefield saying stuff like, “No negotiations. Not until Russia leaves every inch of Ukrainian soil and we won’t even negotiate with Putin. We’ll only negotiate with Putin’s successor after you guys overthrow him.”

I think that especially is one thing that the US has been pressuring Ukraine to stop saying. I think the report recently came out, Ukraine has agreed to stop saying that they’re not going to go negotiate until Putin is overthrown because that’s kind of a pretty escalatory position to take.

The Next Few Months

Richard: Yeah. Okay. So if there’s nothing else we want to say about the recent stuff, we can just go ahead to the…

Chris: Well, let’s talk a bit more about the actual question. What we were just talking about was what the US thinks might develop in the future. Let’s talk about just actually what’s likely to develop over the next few months.

Richard: Okay.

Chris: So in the last podcast we did, I talked about the muddy season and when that was, and the importance of it. I was inaccurate in an important way. I mentioned the muddy season that happens when winter turns into spring and the snow melts. But there is an earlier muddy season that we’re in right now when fall turns into winter. You can get mud then too when the snow is starting to accumulate, but it’s not quite cold enough to be frozen. So we have been in the first muddy season for several weeks now, and that’s one reason why the frontlines have seemed largely stuck both on the Ukrainian offensive and the Russian offensive.

Winter is going to hit in its fullness in a few weeks. I think that that is when we’re actually going to see activity be stepped up. Winter’s going to hit. The ground is going to be frozen. No more mud. And that’s when Ukraine is really hoping to make ground. So here comes the disagreement between the Ukrainians and people perhaps like Milley, who seem to believe that the situation might be frozen.

Everybody knows that winter is going to be hard. It’s going to be hard fighting, but the Ukrainians believe that when conditions become tough for both sides, that will favor them more because they think that they have the better soldiers and the better discipline, equipment. So when a great burden is imposed on both sides, that ends up giving a competitive advantage to the side with the more disciplined troops, which the Ukrainians believe is them.

So they’re really going to be probably becoming more active. I would expect they’re going to throw a lot of their forces into the Luhansk counteroffensive and try to make some significant movement when winter hits in a couple weeks and the ground is frozen and easier to move over.

Another factor is night vision. I read that in the height of summer, there’s about 16 hours of the day where the sun is shining. And then in the depths of winter there’s only nine hours a day of sunlight. So night vision becomes important. The Russians have basically no night vision equipment, almost none worth speaking of. Ukrainians have somewhat more and have the potential to be supplied more by the West. So more disciplined troops caused by a stronger, better NCO corps.

That’s one thing we haven’t talked about in all of our podcasts. Ever since the initial Russian invasion in 2014, one of the main ways that the West has been helping Ukraine is by training their NCOs, their non-commissioned officers. And basically, it’s well-known that the NCO corps is the backbone of an army. They’re the sergeants, the ones who actually basically lead the individual squads and patrols of troops.

So in a Western, NATO style army like Ukraine possesses, it has much stronger, more experienced NCOs that are more comfortable taking the initiative. The Russian military structure really lacks that. And so they’re led from the top down. And so that’s one reason why Ukraine believes that winter will favor it.

Richard: Why doesn’t Russia have night vision? Because up north if they were going to fight a war against the Baltics or Finland or something, I mean it seems like this is something they would need, or Ukraine apparently.

Chris: Yeah. I mean, look, I’m sure they’ve got some. I’m sure that the Russians Spetsnaz has all the best stuff, but I mean if you just look at how their mobilized men are being equipped, they’re not even given the basic stuff. They’re barely given uniforms. They’re not getting fancy stuff like night vision.

Richard: Okay. So we’re going to find out, I guess in a couple weeks, once this mud turns into a frozen ground and we’re going to find out whether Mark Milley is right or the Ukrainians are right, or potentially even whether the Russians can make anything out of their mobilized men, right? In a month, you think we’ll know a lot more than we know now, or maybe two months?

Chris: In about a month we’ll be firmly into winter. And so we will start to see whether Ukraine’s theory of its own victory is correct. Ukraine is confident that winter will favor it more than Russia because of its discipline and its motivation.

How Ukraine Can Win

Richard: Okay. So we should move on to...that’s what’s going on now. We want to talk about how this thing ends. So I think we should talk about Ukrainian victory, what a Russian victory or victory of sorts will look like. And then sort of a stalemate. I want to just go through there. So give me the case for how Ukraine wins in the next, I don’t know, whatever time frame you want. Just give me the optimistic scenario.

Chris: Okay. Optimistic scenario from Ukraine’s perspective, it’s correct that winter favors it more. It breaks through Svatove and Kreminna within the next couple months. And after that, it sweeps up all of this territory in Luhansk all the way up to Starobilsk like I’ve been talking about. It successfully defends and holds off Russia’s assaults in Donetsk. And what’s more, it successfully continues to pressure Russia so much that Russia keeps sending mobilized men to attack in Donetsk too early.

So Ukraine keeps getting to chew them up and spit them back out. And Russia in its desperate effort to keep up the momentum keeps sacrificing more and more lives. Instead of taking the time to really train and assemble its mobilized men into a fighting force. Best scenario for Ukraine, part of its theory of victory, maybe at some point it seizes an opportunity to launch a counteroffensive in Zaporizhzhia and it drives to the coast and cuts Russian territory in Ukraine into two. And after that happens, it’s simple for it to sweep up the remaining Russian territory in the south and even Crimea.

And so the great Ukrainian theory of victory during all of this, with each victory that Ukraine gains on the ground, the West keeps giving it more and more military aid and the Russian will to fight becomes more broken and Russian civilian resistance becomes stronger and eventually pressure rises so high on Putin that he’s forced to concede for at least some token concessions. I do not believe in Ukraine’s heart of hearts that it really believes that it can force Russia to abandon every inch of Ukrainian territory. That seems like a little too much for anybody to genuinely believe.

Richard: Yeah. I mean, the Russians seem to have bad morale. It seems to be getting worse. I mean if you watch the videos from Russian TV on Twitter. I mean, I don’t know how they continue this war effort. I mean they’re all so pessimistic. They’re all like, “We're losers. Everything is going in a terrible direction.” They seem to know this. We haven’t seen them fight... We saw how much Ukraine fought for Mariupol. We haven’t seen them hold out and do urban warfare anywhere. If Ukraine starts just to go on the offensive, I mean, is it possible... given the... just because we’re doing this exercise, we’re talking about what Ukrainian victory would look like and we might as well go all the way.

Is it possible that the whole thing just sort of collapses just because there’s no morale and things are more rotten than it seems and that’s all just being covered up by the muddy season?

Chris: This is a theory we could think of. So realistically, even at best during winter, Ukraine could not possibly take all the territory Russia controls. I mean, even in the absolute best possible case during the next few months, Ukraine might take maybe a third of the territory Russia still controls. And then the muddy season, then the next muddy season will hit where winter turns to [spring] and things will slow down then.

That will buy Russia more time to build up more defenses and finish the training for more mobilized men. At that stage, even under the best conditions for Ukraine, Russia is going to reinforce some of this Starobilsk line in Luhansk and reinforce whatever other regions it still controls. And so even in the best case for Ukraine, I don’t see any scenario within the next few months where it just breaks Russia and sends all of its troops running back to the border.

Richard: Maybe not in the next few months, but who knows how sustainable...

Chris: Basically, I can’t even really pretend to see beyond the next muddy season.

Richard: Okay. So that’s part of the disclaimer here. You’re thinking of just a few months tops because who knows what’s going to happen. Ukraine, I mean, the Crimea thing, if they say they wanted to, there’s only one road to get to Crimea, right? It seems to me that there’s only one road. It seems to me this would be very difficult. You need either a Navy or you need just... There’s just one place you can go, right? I mean there’s not a lot of ways to get there, right?

Chris: Well, yeah, there’s driving south through Zaporizhzhia, going through, how do you pronounce it? Melitopol?

Richard: Okay. So you can do this. So there’s more than one. I see a few roads. The Melitopol road, that’ll take you to Crimea. Okay. I mean, that’s all land. That’s all a...

Chris: It would be probably the most devastating thing that could happen for Russia, would be for Ukraine to launch a successful offensive south in Zaporizhzhia. I mean, if it did that, then it could cut off all the remaining southern territory that Russia controls. Russia would lose so much. I mean that tactical situation is obvious to Russia. And so it has strong defenses here. I mean many of the troops that it withdrew from Kherson, it’s probably positioning them right here to stop that development.

If anything, I think Russia perhaps is more likely to go on the offensive here. Some of the more intense fighting that we have seen rumors of in the last couple weeks is actually this tiny town. Let me try to locate it. It’s called... Oh, right here, Pavlivka. You have to zoom in pretty far on the map to even find this town. But this is where a lot of the fighting has been reported to have been happening. Some of the bloodiest fighting where Russia has been on the attack.

So it’s kind of interesting when you zoom out and say why this little town? Why has this been the center of Russia’s assault for the last couple weeks? So we Zoom out, we lose it, but it’s right here. I think that maybe one thing that’s going on... First of all, you have to consider the rail supply line. So as we talked about last time, there’s really only one reliable railroad running through here and Russia can’t make great use of it right now because it’s too close to the front.

They had the rail line running through the Kerch Bridge. That has been damaged and activity has been tamped down there and it’ll take a while to repair it. And they can’t fully really use this rail line because it’s in the range of Ukrainian artillery. So attacks in this region, I think the significance of them, Russia wants to snap up this territory. One reason it wants to snap up this territory is that if it does, it gains the use of this rail line, which is crucial to supplying this region.

And second, potentially if Russia places the pressure on Ukraine in this Zaporizhzhia region, between Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk, potentially that could lower the possibility of Ukraine launching its own offensive in this region. I think maybe Russia has decided it doesn’t want to be on the defensive here. Maybe it wants to go on the offensive.

Richard: Yeah. “The best defense is a good offense.” Okay. So that’s sort of the Ukrainian thing. I mean, could it do something where it takes this territory of the south and then it can shut Crimea... because Crimea is connected by a bridge and that’s the bridge that was damaged in that attack all those months ago. Was that guy, did they put it in there without his knowledge? Did we have reporting on how that worked, the Kerch Strait attack?

Chris: I’m not sure what you’re asking about.

Richard: Remember that guy with the truck bomb?

Chris: Yeah.

Richard: Did we get reporting on whether that guy was just... Did he know what was happening?

Chris: I have no idea.

Richard: Yeah. Okay. So could Ukraine potentially... Is there anywhere it could get where the HIMARS could reach the bridge between Crimea and mainland Russia and could it shut Crimea off? Or is it just too impossible because Crimea is...

Chris: I mean, you’re talking about HIMARS reaching the Kerch Bridge?

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: That can’t happen without ATACMS.

Richard: Without what?

Chris: ATACMS. The short-range ballistic missile that HIMARS supply that we have not been giving to Ukraine.

Richard: So Crimea is safe I suppose because it can always be supplied from the mainland, right? That’s the situation in Crimea. So if the US gave Ukraine the ATACMS, they could potentially maybe hit more things. I mean they could probably hit Crimea, other places in Crimea.

Chris: They could. I mean they keep asking for it. I think we still haven’t given it. Now, I will say this. I have to look into this more, but in the latest aid package we gave them, there were some remarks that Biden made. There was a little bit of talk about us giving them access to some kind of missile that had a range of, it was something like 160 kilometers, which is almost twice the range of the GMLRS missiles HIMARS is firing. I have to look into that more. Whatever it is, if there’s any truth to that, the US is being tight-lipped about what exactly we’re giving them. But there are starting to be rumors that we’re giving them something that has a bit longer range than HIMARS typical missiles.

Best Case for Russia is a Stalemate

Richard: Okay. We talked about the Ukraine, the optimistic scenario for Ukraine. What's the optimistic scenario for Russia?

Chris: Optimistic scenario for Russia? So first of all, it’s that Ukraine doesn’t make significant progress during winter, that Russia’s soldiers hold up well enough. I think the reasonable best case for Russia is that winter is mostly a stalemate because it’s still got this large wave of mobilized men. Maybe you’re in the neighborhood of 200,000 of them that are still in training. I think the best case for Russia is that it holds out through winter and large waves of mobilized men hit and then they make a real difference going on the offensive in say Donetsk.

And let’s focus on Donetsk because I think the indications are that that is what Russia is hoping to gain. So the realistic best case for Russia, I think is that it succeeds in that it holds out through winter. Its mobilized men hit, couple hundred thousand of them trained, and it manages to take most or all of the remainder of Donetsk, holding basically all of Luhansk.

Meanwhile it’s used Iranian drones and ballistic missiles to step up the pressure on Ukraine’s infrastructure. It can also hope that winter is cold for most of Europe and that Europe really feels the sting and that the casualties rise so high that the Western voices urging Ukraine to negotiate keep becoming louder. And Russia’s hope is that Ukraine runs out of victories to keep showing its Western backers.

Right now every time Ukraine gets a big victory, it takes that to the Western backers and says, “Look at what we’ve accomplished with what you’ve given us. Here’s how much more we could accomplish if you give us even more.” Russia will hope to deny Ukraine the ability to say that, to stop its momentum. And if it blunts Ukraine’s momentum, then the spigot of military aid starts to get a bit drier and then the momentum starts to shift even more.

Richard: I just don’t see it. I mean, it’s not that expensive with how much they’re supporting Ukraine given the... It’s not like the Western countries are spending all of their GDP on Ukraine. The economic damage is much worse that they’ve suffered already than the direct cost of military aid. So why would anyone think that the Westerners are going to stop supporting Ukraine? It just seems to me... At least America, very highly unlikely.

Chris: I think the main reason to think it is just the existing voices in favor of it. I mean, you could argue that you see the beginnings of a trend with some Republican voices like Kevin McCarthy having talked about how they might potentially start cutting back on...

Richard: I don’t think that’s very serious.

Chris: The truth is, you’re right. We can say, “Oh, we’ve given billions and billions to Ukraine.” I mean, we’re the United States of America. Biden waves his hand and spends 400 billion on student loans or something, even though it's not actually happening as of right now. But when you look at the scale of the programs that we pass for ourselves, like 19 billion in military aid is kind of a rounding error.

Richard: Yeah, that's what I’m saying. This is not a very costly operation given how important the US apparently considers it.

Chris: And not only is it a rounding error, but I think we have to be a bit more cynical than people allow themselves to publicly be on this topic to really understand the US interest. It’s not even that the aid is a small amount, it’s that pragmatically the military aid is a great investment for us. We buy those rockets imagining them being used by American soldiers to kill Russians. Instead, they kill Russians with no American soldiers dying. I mean, the truth is it’s kind of a good bargain for the United States, this proxy war.

Richard: I mean, depending on the global impact. It depends on what your goals are. If you care about maximizing GDP, the health of the global economy, maybe not. If you’re scared of Russia, if you just want to weaken Russia, then yeah, it’s a good investment, right? It’s not that clear depending on exactly what you want. The foreign policy establishment might be one way and Biden might have a broader view or a humanitarian view or an economic view and think something different.

Chris: Maybe. Another consideration is oil prices. The end of the war, one of the main ways that would probably benefit the global economy is to release some pressure on oil prices so that the gas price could come down. I think that the midterms being passed now makes gasoline prices a little bit less of a factor in Biden’s thinking probably.

Richard: Yeah. Although 2024 is right around the corner. So Anatoly Karlin on Twitter was talking about what a joke it was that Russia was only spending 5% of its GDP on the military during this conflict. Is there a potential bigger mobilization that Russia can do down the line, a complete war economy, a general draft? It seems like they are... they’re still fighting like this is the conflict in Georgia, like it doesn’t mean that much to them, but it seems like what they say, what they’re doing don’t seem to match.

They talk about this as a great conflict, that they’re defending Russia territory and then they’re only spending 5% of GDP on the military. Is there potential for Russia to double or triple that and then maybe give themselves a way to go on the offensive?

Chris: I suppose it’s a theoretical possibility. I’m not sure it’s a practical possibility because look, we’re already seeing rising Russian civilian resistance to the war, rising public criticism. I mean, after the retreat from Kherson, we’re starting to see more and more personal criticism of Putin himself.

Richard: Well, you see criticism from the other direction too. You see criticism that they’re not aggressive enough in fighting this war and they’re not asking for enough sacrifice.

Chris: But personally, just when I process all of the reports that I see of the Russian attitude, I think we are reaching the point where a lot of the mobilized men have started dying already. And so the punch of that is starting to land to the friends and family of those mobilized men. I think that that is only going to increase. So in theory, Russia could potentially mobilize more people.

I think that for Russia to really justify that to its populace, it has to be able to show that it’s not just sending them into the meat grinder. It has to show concrete evidence that it’s making gains through these mobilizations. It has to justify them.

Richard: Yeah. And there’s no switch you could flip to guarantee that because they don’t have superior weaponry. So it’s like what can they do? It doesn’t seem like there’s a way to guarantee that for the population.

Chris: Yeah. So we were talking about best case, best realistic case for Russia. I think one important factor will be the quantity of Iranian aid. This is up for debate right now. As reports came out in the media that Iran was starting to send a lot of short-range ballistic missiles and more drones to Russia, Iran started coming out saying, “No, no, we’re not. Not a big deal. We sent them some stuff, but that was before the war started.”

It’s largely cut off from much of the world economy, but I suppose not entirely cut off because Iran seems to be feeling the public pressure not to substantially aid Russia. Somehow the West must still have some economic leverage left over it.

Richard: Yeah, that’s right. There’s always the Chinese aid. I mean who knows if that’ll ever come, but that does…

Chris: China has shown no inclination of wanting to send military aid to Russia. China seems to be moving more and more in the direction of distancing itself from Russia. I mean it’s been making more public statements. Xi Jinping just made this joint statement with Biden, no nukes in Ukraine and no threats of nukes either. By the way, we have seen Russia backing down from all these nuclear threats over the last...

Richard: Yeah, that’s right. I was going to ask you, after best case for Russia, I was going to ask you what’s the case for a stalemate? But it seems like that’s the same thing. It seems like you think the best case for Russia is the stalemate.

Chris: Yeah. I think the best case for Russia begins at least with a stalemate. A stalemate over the next few months. And then its hope is that after Russia creates a stalemate, then it blunts Ukraine’s momentum. When it blunts Ukraine’s momentum, Ukraine can no longer justify getting increased military aid from the West. As that decreases, Western pressure diplomatically on Ukraine increases to negotiate and with the combination of those and then the mobilized men hitting for Russia in a couple months, it could hope potentially to make some advances on the battlefield, especially taking Donetsk. I think that's what Russia is hoping for. In the short term, advances in a couple months after mobilization really pays off.

Richard: And so far…

Chris: If Iran helps to arm it especially.

What Peace Looks Like

Richard: Yeah. At some point, there’ll have to be a peace deal. Let’s say there is. So it’s going to depend on how much Ukraine can actually take back, what it could actually gain on the battlefield, whether Russia could take anything. What do the outlines of a deal look like? So I think from what I see, it’s very strange. I mean, it’s just very strange that Russia annexed Kherson and now does not have Kherson obviously. It allowed an out for itself that it had never said what the borders were of these regions.

So it could still say we have Kherson and we just call, consider Kherson the east side of the Dnieper River and they can say, we consider Zaporizhzhia, just whatever we hold. And we consider Donetsk and Luhansk... Right? I think it would have to have at least one inch of each of those four territories to sign any kind of peace deal. I mean, how does Russia sign a peace deal that doesn’t have it... We talk about Ukraine, whether its people... How would Russia sign something that gives up part of its territory? How does it do this?

Chris: I think Russia can always rewrite the narrative to favor the facts on the ground, as far as PR goes. I mean, look, if it loses more of the Kherson region, it can always... If it comes to it, you can always sign a deal saying, “Look at what we’ve got. We went into this war wanting the Donbas, we’ve got the Donbas and we still have Crimea. We’ve won.” It could always say that.

Richard: So they have an unlimited ability to shape the narrative? But if that’s true, couldn’t they have... We just said that they can’t just brainwash the people to have a total war and invest huge sums of money and treasure. But it seems like they can... It seems like you think that there’s pressure coming from one side. There’s pressure towards peace coming from within Russia, but there’s not pressure for more aggressive action.

Chris: Look, there are always going to be hardliners who say, “No, Kherson was Russian territory. We cannot sign a treaty giving Russian territory to the Ukrainians.” And there will be those voices. But I think the facts on the ground can successfully drown out those voices if it’s just not possible for Russia to take those territories.

Richard: Yeah. So you’re saying that these people will sort of... I mean you could tell a different story where the more they lose, the more the hardliners get empowered. The more cornered Russia feels, the more it wants to... The more people who just want to go total war and start doing all kinds of crazy things. But I guess one reason to think that that’s probably not going to happen is because of the trajectory of it. You would have thought maybe Russia is losing territory, maybe they become more serious in its nuclear threats. But we’ve seen the opposite as it’s gotten weaker. The size of its bark has decreased, right?

Chris: Yeah.

Richard: So it seems like we are on a trajectory towards Russia becoming less ambitious. It’s so stupid because the peak of their ambition was when they annexed those four territories, which was like they were on the downwards slope of their military success. They had already lost a bunch of territory and then that was the peak of their ambition. It seems like since then they’ve been scaling back their ambition to more closely match the battlefield realities.

Chris: That’s true. I think that you could actually use that as part of the narrative of the best case for Russia. Part of the narrative of the best case for Russia would be that it’s been starting to make some sounder strategic and tactical decisions like this withdrawal from Kherson which apparently happened in fairly good order. As part of the positive case for Russia, you could say, look, they’re starting to fight smarter. They’re starting to be more realistic in aligning their political goals with their military capabilities.

If they do really limit their ambitions to taking all of Donetsk, and they funnel all their mobilized men toward that and they funnel a lot of these withdrawn troops from Kherson to that, you could make the case that Russia could have success in achieving its scaled back ambitions.

Richard: Okay. I mean, if you get any territory internationally recognized, I mean that could be sold as a victory. It’s like a utility function where it’s just total land, like land gained over the course of the war and whatever. You’re in the black. You could be happy, I guess.

Chris: Yeah. I do not think that Russia is limited by its annexation announcements to what it can ultimately accept in a treaty. I don’t think it’s going to be like, “Oh no, we can’t sign this treaty because we annexed Kherson...”

Richard: I mean, do the words that the government says in their ceremonies, do they have no meaning at all in the grander politics? Could they just say, “we annexed Washington, DC and it’s part of Russia”? And then forget that it ever... They had a signing ceremony. I watched it. They had a big speech. They had all these dignitaries. So it’s a big deal.

Chris: It can be forgotten if it’s in most people’s interest for it to be forgotten.

Richard: Yeah. Could the US just forget? I guess we could. I mean, we could forget Afghanistan. We could forget Iraq. We couldn’t forget that Florida is part of America or something. But I think we could. Maybe you’re right. Yeah. Okay.

Chris: I think that as far as what Russia will get at the end of this, I’ve been saying from the beginning that I think one of the first concessions on the table would be Crimea. And I think several months ago back when the two sides were at the negotiating table, that’s one of the things that Ukraine itself was talking about. It was talking about some kind of deal that would essentially in all but name leave Crimea under Russian control.

I think that that’s probably what’s going to end up happening in a deal. Ukraine has been saying a lot of talk lately in the news about how it’s going to assault this territory and take it. And that’s part of the role that this offensive in the Kinburn Split plays. It makes credible the Ukrainian threat to take Crimea. I think ultimately this is kind of a negotiating ploy. Ultimately like, “Oh, we’re going to take Crimea. We’re going to take Crimea.”

They say that so it can be a major concession they can give up. At least some of them may be thinking that way. Probably others are sincere in saying, “No, we’re going to take everything from Russia.”

Richard: Okay. What is the minimum that Ukraine could give up? So Crimea we said. I mean, could Ukraine give up like Mariupol? Could it give up parts of Zaporizhzhia if Russia holds off? I mean, is that something you see as realistic?

Chris: So in Zaporizhzhia, one thing of significance is the nuclear power plant, the very large nuclear power plant there. I think Ukraine will want to end up with that no matter what. But that’s I think relatively close to the...

Richard: Yeah. There’s a danger in trying to take that though...

Chris: So in any kind of negotiations, perhaps one of the concessions Russia could make Ukraine is that it gives Ukraine back some of this territory up to, including the nuclear power plant there. I think Ukraine will want that no matter what.

Richard: Yeah. Could they give up Melitopol or Mariupol? Could they give that up?

Chris: I think it would be a pretty tough pill for Ukraine to swallow, giving up either of those. And I think it would do that very begrudgingly. I think it’s pretty unlikely that Ukraine would want to give up either of those major cities.

Richard: Donetsk and Luhansk, I guess that’s in between. You think probably at least those cities they could give up?

Chris: Potentially. Potentially Ukraine, I mean certainly Luhansk over here. Much of the area in the Donbas close to the Russian border. I mean in whatever deal eventually materializes, some significant amount of the Donbas will end up remaining under Russian control, I believe.

Will the West Ever Pressure Ukraine?

Richard: Yeah. How do we get to negotiations from here? Because each side sounds absolutist right now. I don’t know if... Are we in the West... Who knows about Russian politics, but are we in the West, are we capable… is Ukraine capable of negotiations? I mean, this is a recurring thing. Didn’t Zelensky want a little bit more of an accommodationist policy? And he was pushed into being a little more hawkish by the hardliners before the war. Isn’t that a much bigger problem now? It’s just hard for me to imagine a breakthrough of them sitting down and talking this out.

Chris: I think Ukraine in general, Ukrainian higher-ups seem fairly unwilling to negotiate. And so I think the United States, we see the signs that the United States behind the scenes and increasingly in public is starting to nudge Ukraine saying, hey, basically we seem to be starting to tell Ukraine, don’t take advantage of us. Don’t think that we’re giving you a blank check and that we're just going to fund you to attack Russia for decades with you making no concessions.

We seem to be starting to send Ukraine that message. I think for Ukraine, a lot of this comes down to whether its theory of victory can hold up during the winter. If Ukraine is correct that it can make territorial gains during the winter, then it probably ends up... It can keep playing, essentially. It can keep going. We give it more. But if Ukraine is incorrect and it’s a stalemate during the winter, then probably the pressure rises and we start telling them, it’s not a blank check. You can’t keep saying these things like Putin has to be overthrown and all Russian boots have to leave every inch of Ukrainian territory.

This is something where you and I might agree on this. I think that a lot of the pro-Ukrainian commentators in the West, they’ve fallen into a bit of cheerleading. They take this kind of moral view that we have no right to tell Ukraine it has to come to the negotiating table at any point. So there’s this one phrase that’s been making the round for months that expresses the cheerleading side.

It’s the phrase where people like to say something like, “If Russia leaves Ukraine tomorrow, or if Russia stops fighting, the war ends. If Ukraine stops fighting, Ukraine ends.” And everybody says that. It’s this very telling point, this irrefutable argument, an argument supporting the side that there should be no pressure on Ukraine to negotiate. And to me, it just sounds like cheerleading. I mean, of course if Russia… it’s literally true.

But what does it actually prove? I mean, yeah, of course, I think that Russia is the one who started the fight. But you can’t just have this childlike insistence. “Russia started it. It’s on Russia to end it. It’s not on us to end it.” I mean, that’s kind of playground reasoning.

Richard: Right. But the question is whether that has relevance, whether American leaders and Ukrainian leaders are thinking along those lines, in which case this could be a very long war, right?

Chris: And I think that at some point, I think the West is not going to allow this to turn into a new World War I. If it becomes a stalemate and is just trench warfare, and imagine this, hundreds of thousands of people on both sides dying going forward. Suppose we reached the point, are we going to allow it to come to the point where there’s more than a million dead soldiers...

Richard: I mean, we don’t care about the casualties so far. I mean, I don’t know why that would pressure us. That would be a question for Russia and Ukraine. I don’t think an order of magnitude more deaths in Ukraine is going to... You might have thought that now we’ve had tens of thousands. I don’t know what the casualties are. We could have thought that we wouldn’t have let that happen. I don’t know why we couldn’t let hundreds of thousands. I don’t see what the limiting factor is here.

Chris: Well, there’s a couple things. First of all, there’s our interest in the oil situation. Our interest in peace is connected to our interest in the global energy supply. Secondly, there’s the fact that our supplies of ammunition are running perilously low and we don’t really want to step up production. At the same time, we’re looking at Taiwan and we’re looking at China and thinking we’re going to need that ammo if any action there comes up. At our current stores, we cannot keep up this pace of aid. We only have so much HIMARS ammo. It’s also about the money.

Richard: Yeah, it costs money. But why can’t we just... I mean, we said it’s not that much. Why don’t we just invest more in ammo? Taiwan, China, who knows if we’ll actually see that war. As far as the energy stuff, you could imagine global supplies like adjusting around the reality of the war. You could imagine there’s stuff always in the works. The market adjusts. Markets tend to adjust very well towards these kinds of things. So maybe it doesn’t hurt that much. I guess I’m giving you the case for the war going on forever.

Chris: There’s also our humanitarian interest. I mean, set aside our cynical self-interest. What is our interest in seeing tens and hundreds of thousands more Ukrainians civilians and soldiers dying, if there’s no progress on the ground?

Richard: I mean, we could have told Ukraine before the war, we could have done a more serious negotiation if we care so much about humanitarian issues. I think we would’ve done a lot of things differently. I think we would’ve tried harder to avoid the war. I think we could have argued for concessions that are going to end up being in the peace deal, probably like give up Donetsk and Luhansk, whatever the Russians have, and Crimea and no NATO. If we were really humanitarians, I mean, I think we would’ve done that, but apparently we didn’t.

Chris: I mean, we were wrong about a lot before the war started. But war is a big drag.

Richard: I don’t see humanitarian suffering of Ukraine being a major... It is in the sense that it drives anger and hatred towards the Russians. I do see that, but I don’t see a cool rational consideration of how to reduce the suffering of Ukrainians being at the forefront of our thinking.

Chris: At some point, all these costs start to add up. The cost of the aid we give them. Sure, it’s not that much so far, but do we really have an interest in sending them 20, 30, 40 billion a year indefinitely when all it’s producing is more dead on both sides, more devastation and the frontlines are staying the same in trench warfare?

Richard: Put it this way. We spent 20 years in Afghanistan, Iraq, we spent trillions and those were American wars directly, but the public, especially after the first few years, wasn’t paying that close attention to any of the wars. So these wars were not as important to us as Ukraine is just given how much attention we give them. And we were willing to spend orders of magnitude more than a couple, 20, 30 billion a year on Afghanistan and Iraq.

So if it’s harder to end the support for Ukraine, just because Ukraine is more of a standard of something that everyone in America supports. If we could do Afghanistan and Iraq for 20 years and spend all that money, why can’t we do Ukraine, for a fraction of that?

Chris: What do we get out of it?

Richard: Nothing! What do we get out of Afghanistan and Iraq? People just read the paper and they care about Ukraine and they want to cheerlead for Ukraine for the same reason we want to win in Afghanistan and Iraq. I don’t know what we got. I don’t know what we would’ve gotten, even if we won. I don't think we would’ve gotten much.

Chris: If you look at polls of American support for aid to Ukraine, isn’t there already a discernible trend of decreasing support in our polls?

Richard: Well, I mean the Afghanistan war went on for like a decade after it was pretty unpopular. Yeah, there could be. But still just by a benchmark... like the taboo on not supporting Ukraine anymore seems to me to be much stronger than the taboo was say 10, 15 years ago of pulling out of Iraq or Afghanistan. There were more voices able to call for that than there are people saying, “Don’t support Ukraine anymore.” And so that makes me think it’s subjective. You’re asking, “What do we get out of any of this?” Who knows? But subjectively, it’s more important to us. I tend to think we can just provide that support indefinitely.

Chris: I mean, our wallets are capable of continuing to indefinitely send 20, 30 billion a year, I mean even more to Ukraine. I mean the American economy can support that. But I just look at the existing trends. That’s part of what’s informing. I’m looking at the trends of what the US is starting to do, and the US is starting to become increasingly public in telling Ukraine that, we aren’t willing to give them a blank check indefinitely. And it’s not any one particular party in the US either. We’ve seen incipient signs of it in the Republican Party. We see hints of it cropping up in the Biden administration.

Richard: Yeah. You might be right. These things have a mass psychology to them. And we don’t even know. I think even if the Biden administration thinks that it wants a negotiation, I don’t know if it itself has a good sense of what it actually looks like, what the pressures actually are when the rubber hits the road. So when’s a good time to negotiate? When Russia makes an advance? No, that’s dangerous. We have to stand up to them. When Ukraine makes an advance? No, we’re pulling the rug from under them. Just when they’re making advances we’re... So it’s actually, they may want this in the abstract, to find some kind of peace deal, but practically it’s hard. These things have a way of just dragging on.

Chris: So I would say that the time to negotiate is not now.

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: It’s not now because Ukraine has the momentum now. And so Ukraine should continue to see how far its current momentum can take it. A lot of the stuff in this war reminds me of this old saying that people attribute to Lenin. “Push the enemy with a bayonet. If you hit flesh, keep going. If you hit steel, stop.” And I think that the Ukrainians, all they’re hitting is flesh so far, so you need to keep going.

Richard: Okay. So I think we agree that as long as the lines are moving, as long as there’s some movement, peace is hard. A stalemate is the best thing for achieving peace, right?

Chris: Yeah. This goes back to the thing I was saying about how political considerations have been playing such a large role in the strategic decisions on both sides here in this war. We’ve seen and talked about how Russian political considerations have dictated where they attack and where they retreat. And with Ukrainians, there’s this bargain. They know that, basically the Ukrainians through their actions have made it clear that they believe they need to keep advancing. They need to keep winning victories that they can take to the West in order to get continued military aid from the West.

That’s one reason why at the beginning of the Kherson offensive Ukraine was losing a lot of lives. I think Ukraine lost more men than it needed to at the beginning of the Kherson offensive, because ultimately the strategy that won the battle was not advancing, right? The strategy that won most of this was the strangulation strategy.

But Ukraine did not rely on the strangulation strategy from the beginning. At the beginning in the first couple months of that battle, it did a lot of advancing and it lost a ton of lives in those advances. And I think that that was dictated in part by the political considerations where they felt we have to show the West that we’re advancing. And so that dynamic continues to hold true, and Ukraine is going to continue. I mean, it bought itself a little time with this major victory in Kherson, but my sense of the war so far is that the West is going to start to get impatient if Ukraine doesn’t show any significant advances during the winter, the next couple months.

Richard: Yeah. I think I disagree. I think that especially if there’s a Republican in 2024, I think that the Republican Party will be much... You think, you take the anti-war sort of noises in the Republican Party a little more seriously than I do. I think the actual political people, the people who will be staffing the State Department, Defense, are going to be extremely hawkish. And I think that holds for Trump, maybe especially for Trump, because there’ll be so much pressure.

The reason why Trump gave Ukrainians lethal aid in the first place, because he was so constrained by politics. He couldn’t do anything to be friendlier to Russia. So I think that what you’re saying makes sense, but I think I am... If we’re going to sort of estimate, I think the war is going to last longer than you do. I think the ability or likelihood of the West to impose peace on Ukraine, it’s difficult for me to see.

Chris: There’s also people like Elon Musk. In all these podcasts, we haven’t talked about the Musk factor, but the Musk factor, the Starlink factor is actually somewhat important to what happens on the ground.

Richard: Do you think he’s going to cut it off and then make...

Chris: I think that at times Musk has cut off Starlink already. There have been lots of reports here and there of Starlink access mysteriously disappearing for the Ukrainians.

Richard: So you think he calls someone and says, “The Ukrainians angered me on Twitter.” You think he does that? I don’t know.

Chris: What I have seen is that when... There’s a strong correlation, when Elon Musk is unhappy at Ukraine, they seem to have an increasing number of Starlink troubles.

Richard: Maybe that’s when people notice them. It’s like you’re looking for crime and then people think, “Oh, Elon Musk is fighting with Ukraine.” Every potential snag in the Starlink system, you start to blame it on that. Maybe it’s...

Chris: That doesn’t fit with the reports that I’ve seen from the Ukrainians themselves. I mean, I’m going off of official statements I’ve seen from Ukraine that to me imply that Elon Musk has been cutting off their Starlink access at certain times based on his disputes with them. And so first of all, Starlink is critically important to Ukraine’s ability to advance. A lot of what it does is predicated on Starlink.

Richard: And the HIMARS have internet. They need internet? Is that it?

Chris: Yeah. It’s not just the HIMARS, but Ukraine, one of the ways that it’s been overcoming its quantitative disadvantage in artillery compared to Russia is through using its artillery very smartly through this network of drones linked up through Starlink to guide the guns and do spotting for the guns. Starlink has allowed Ukraine to use its artillery, kind of like sniper rifles. And every time Starlink access cuts off, Ukraine stops advancing.

I don’t think that Elon Musk is going to allow Ukraine to take Crimea. From everything he said, I think that if they tried to take Crimea, they’re going to do it without Starlink.

Richard: Yeah. You say that’s the report from the Ukrainian government and they could be subject to the same bias. Maybe the system goes down every so often. And then when Elon Musk is fighting on Twitter, it’s like you fight with your power company and then the power goes off and you think it’s related, but maybe it’s not. Maybe the power goes off a lot of times and it’s not necessarily that. It’s just hard for me to see that. I mean, he has to pick his battles. I mean, he’s fighting over the Twitter stuff about they wanted him to censor more on Twitter. He’s a very courageous man if he’s also willing to push back on Ukraine too. That actually…

Chris: The particular exchange I’m thinking of is when Starlink access was cut off, Elon Musk was posting stuff like, “Oh, we don’t have enough funding to continue just giving Starlink to them for free.” Suddenly all the terminals in Luhansk were cut off. And then I saw this tweet, this tweet from a Ukrainian government official high up who was saying, “We will make a deal with Elon Musk, but we need Starlink access to continue while we are negotiating that deal.” He strongly implied he cut it off.

Richard: I think he just wanted the money and he just didn’t want to keep providing it for free. Maybe it got worked out. Maybe they paid him.

Chris: It’s not just that. This was back at the height of the nuclear tensions. So Musk seemed to be strongly implying he was worried that if Ukraine never negotiated, things might escalate to the point of nukes.

Richard: Yeah, maybe he worries about that, but maybe he’s forgotten and he’s moved on to other things too.

Chris: But anyway, look, in general, I just think I see the signs from various parts of society that Ukraine does not have a blank check from us indefinitely and Ukraine’s own actions are consistent with Ukraine believing that it needs to make battlefield progress to continue getting support. Ukraine seems to believe that.

Richard: Okay. So Chris, I defer to you on the war stuff, which I don’t know much about. On the politics stuff, we have a difference of opinion, but we’ll see what happens in the coming... I think we could summarize this as you think, probably, maybe by spring, by summer we’ll start to see the outlines of the end of this. And I think probably not. Is that our disagreement?

Chris: So remember what I’ve said is that as far as what happens on the ground, I can’t see much farther than the next muddy season. But if I try to look farther, I will say this, here’s where we seem to disagree. If the front lines are frozen and the deaths are accumulating on both sides for the next year, I think that support for Ukraine will dwindle if there’s a long stalemate that’s bloody for everybody. I think that that dwindling would eventually bring it to the negotiating table.

Richard: I don’t think it’s impossible it gets to the negotiating table. But I think Ukraine itself will want to go to the negotiating table before the US and Western Europe cut it off because it’s being hurt much more. I think given the political realities here in the West, I think there’s enough money and there’s enough resources to keep this going. But eventually Ukraine is going to have to sit there and think, just going to this meat grinder in World War I kind of trench warfare situation, how much longer do we want to do that? Right? Ukraine is going to have to eventually figure that out. So I would expect that Ukraine and Russia would come to an agreement before the pressure came from outside.

Chris: We will see.

Richard: Okay.

Chris: I do think at some point, I think, Ukraine will not continue to hold the momentum forever. It’s not going to drive Russia all the way back to the border.

Richard: Yeah. Okay. Great. So I think that covers it. Chris, is there anything else you want people to look out for? Are they going to look out for the month, next month when the ground freezes? Anything else interesting that people should be looking at?

Chris: Just basically over the next two months, starting a couple weeks from now, Ukraine needs to prove its own theory of victory true and it needs to make progress on the ground in Luhansk over the next couple months. The other thing to look out for: is Ukraine ever going to materialize a new counteroffensive somewhere else? I mean, we’ve seen that Ukraine has the resources to sustain two counteroffensives at a time. Now that the Kherson one is done, is it going to open up a new one potentially in Zaporizhzhia? That’s the big question.

Richard: Gotcha. Okay. We’ll be looking out for that. All right, Chris. It’s been fun, man. Until next time.

Chris: Yep, next time.

Video and Transcript: How Does the War in Ukraine End?